Scale and Convention: Programmed languages in a regulated America

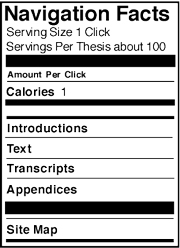

Saturated Introduction: A Program of Contents

This thesis treats a variety of programmed languages in late twentieth century life in America and 'the rest of the world'. It begins as an ethnographic description of a small set of sites in healthcare information technology, where I was entangled in the bureaucratic bathos of a huge academic hospital and experienced the excitement of an internet healthcare start-up company. It ends in many places. As a result, and in order to say some complicated things, this dissertation somersaults through an eclectic set of issues, viewed from a variety of disciplinary perspectives any one of which alone would have missed the connections that I intend to make concerning language, software, standards, regulations, and the internet; it uses the American healthcare industry— in particular that segment dealing with radiological images for diagnosis— to explain the scale and convention of a fluidly programmable international market economy.

What I am calling programmed language includes all of the ways in which language is both meaning and action at the same time. When language is both representational and performative, I call it programmed [1]. This implies first a connection to the empirical fact of the ubiquity of computers, computing, and networked communication in modern life, but also to the similarly ubiquitous fact of design as a medium for constraining, influencing or controlling actions. From the simplest search algorithm to a democratic constitution, programmed language designs constraints on the actions of actors and changes the configuration of organized society, its symbolic structure and the subjectivities of its inhabitants. These are not solely the function of language itself, however, but the character of language that has been designed— that has yielded, however insignificantly, to the actions of other actors and other programs. I find programmed languages everywhere.

Programmed language in technical standards, especially those concerning the specification of telecommunications and software design, (in particular, the internet, which is differentiated from other telecommunication networks and other kinds of software design) is explored both as a representation and as a thing. That is to say, standards are explored as representations that order reality, and as performatives that "do things". My label for the latter: the ubiquitous cry of the happy programmer: "it works!". My research led me to the conclusion that there is an essential difference between two types of standards-setting processes. There is the hierarchical, "consensus-oriented incrementalism" of national and international standards development organizations who have complex bureaucracies that intend standards to be complete, and separate from any mere implementation of them in the real world. Call them Platonic standards, perhaps. Then there is the seat-of-the-pants standardization work of the internet (in particular the Internet Society and its connected organizations) that insists on the existence of two working implementations as the minimum requirement for becoming a standard (which is subsequently no less modifiable). Call them pragmatic standards. It is unclear whether the distinction between these two orders of representation (or between the order of representation and the order of programming) is tenable, but it is the goal of Scale and Convention to investigate this with specific emphasis on the internet, which is not merely one network among others, but is the proverbial difference that makes a difference [2].

Programmed language in software and networking design, especially concerning the concept of openness, to which I was led almost inevitably from the question of standards raised above, via the term 'open standards' and from there to details of how software and networks are open: technically, legally, religiously, and world-historically. Openness comes in all forms, from weak to strong, but it concerns, above all, communicability. That is, openness depends on conventions that themselves are open, freely available and in the furthest case, modifiable by anyone. The structure of such a situation is what the Free Software Foundation and opensource.org find themselves proposing to a software industry entrenched in a world of copyright. The languages of software therefore include the availability of source code, the adherence to the standard protocols of the internet, and a certain ideology of openness that is yoked to a myth of the scientific method. Also important here is the distinction between technical and non-technical. Software, especially the source-code of high-level programming languages possesses peculiar relations to 'ordinary' language that make the distinction between technical and non-technical non-obvious [3]. Standards that govern the communicability of software are what decides between the technical and the non-technical, and it is therefore worth paying attention to the political organization implied by the standardization of software. Openness itself has become that which legitimates an open standard [4].

Programmed language in law, especially that of trademark, patent and copyright law, and of commercial contract law. Law is the quintessential example of performative language, and the investigations of law's legitimacy rarely fails to recognize this peculiar procedural function. Law enters this thesis in two places: first in the form of a lawyer, Larry Lessig, who I take as a kind of foil for a second wave of internet related 'hype' (that concerning the revolutionary power of "open source" software, more below on hype). His discussion of how the "code" of the internet regulates "us" just as much as the "code" of the US congress is a perspicacious entry to the peculiar ubiquity of programming techniques in legal langauge. Copyright, obviously, opens onto a history of the legal regime of property, which will be essential for understanding the problematic distinction between product and service, or thing and person. Trademark, and the gerund "branding" relate the issues of the tangibility or intangibility of property to the legal basis of right to the technical reconfiguration of manufacturing to the power of marketing. In the second section, I take the history of the legal regime of property in the US as an essential background to understanding the possibilities created on and by the internet. The possibility for the variety of "services" and "solutions" that have appeared on the internet forces certain questions not just about the legitimacy of property, but the very source of value as well [5].

Programmed language in regulation, especially the legal implications of a property regime that has moved always in the direction of intangibility of property, towards the guarantee of rights and hence the need for expertise in the discernment of rights to property. The twentieth century creation of an American regulatory state— the delegation of legislative power to private, unelected citizens, and the subsequent erosion of the distinction between public and private governance— is also essential to understanding the role that standards have today as law. The legacy of regulation is its power and its ubiquitousness, producing a situation that some economists now refer to as a 'political economy of fairness.' The history of healthcare as an infrastructure of medical technologies submitted to this complex political economy of fairness should appear as an obvious test case for any description of the current status of the regulatory state and the technical configuration of society. The specific test case drawn from my fieldwork concerns the Company Amicas and the internet service it provides to radiology in healthcare [6].

Programmed language in hype and buzz, especially as it exists in the healthcare industry (and I admit no immunity to it, as I can now say "healthcare industry" without flinching). This language also concerns the descriptive and the performative, or as I prefer, use and mention. There is a tendency to dismiss hype as simply meaningless. This is true, but no one ever confused meaning with force. Throughout my research, I repeatedly experienced the mention of certain terms or turns of phrase that only began to make sense when I tried to watch what they did for or to other people. In some cases, hype is experienced as such, and dismissed by people, without effect. In others, hype actually controls a situation. In the end, hype just becomes language, one learns to speak that way, like one learns to write a certain way, and with due diligence the words that sounded like blabber to begin with, can become either poetry or tool. In my discussions with the members of the company Amicas Inc., (described below) I experienced a transformation of this kind. Chapters P and Q contain some detailed musings based on the words of Adrian Gropper, the CEO of Amicas, that I would have dismissed as hype without a two years experience of the mention, and eventually, use of these words. They concern the structure of the healthcare information technology industry and the replacement of the infrastructure of healthcare by the internet, and are related directly to the langauge of law and regulation and to programmed language in standards and openness explored in Chapters E-M. If at any time I appear to be uncritical of his or others' words, it is most likely because I am.

Finally, the English language is poorly programmed herein, it is an open question as to whether "it works." This might be just a question of style, in the sense of fashion. However, I prefer to imagine that the language of this dissertation takes baby steps towards articulating a thesis that would be invisible in any given disciplinary vocabulary— the nominalopathic colon-enhanced excesses of cultural studies as much as the "narrative clarity" of history as much as the soulless argumentative rigor of law or economics as much as the authoritatively luminous insistences of philosophy. At times I have tried all of these and others, always breaking their rules and always coming up short in vocabulary that would capture what I want to express. This is also a question of programmed language. Ordinary English language (and especially academic discourse) only works because it possesses all kinds of conventions, and it is these conventions we seek when we seek meaning; this begs the question, however, of what conventions mean, how they work, and to what end they are endlessly proliferated. Programming, however, is not simple automation, it is design. Effective design demands good data structures, sound physical principles, or inspired energy.

The design of this thesis, then, is inspired by the genuinely infectious energy of the internet healthcare start-up company Amicas. I began the "fieldwork" for this thesis intending to study the "culture" of telemedicine research, I was confronted instead by a bewildering array of problems involving 'scale' and 'convention'— two terms that I have reduced to primitives, the sound physical principles of this dissertation. I did not, however, find any "culture". It was like a place without a culture, which at first seemed a welcome change to the familiar contemporary problem of cultures without place. I found "culture-change", "corporate-culture handbooks", and culture in the form of Bostonian films, food and theater— but none of these things were at that place (where?). Worse than no culture, even the place (which place?) started to seem unstable, it didn't feel local, it dealt with problems close at hand and far away as if they were all the same. Telemedicine, of course, is all about "overcoming distance" and "increasing access," yet it was not a problem of distance that confronted me, it was a problem of "scale". Scale is both noun and intransitive verb: something can be big or small scale, but when it is both big and small at the same time, then it scales. This scalability, I insist, appeared with the recent massive acceptance of the internet. Reluctantly, skeptically, I call it new. The internet covers the globe in a creep. It is not an imperialist tool, or a viral social process, but the result of hundreds of millions of deliberate individual decisions to participate. It is a convention to which people constantly, provisionally assent. This should raise questions about international and national governance— and about the design of that governance. I reach this question from the example of an internet healthcare start-up company's discovery of this scalability, and its constant struggle with the variety of conventions that enfold it (standards, regulations, law, and customs). I offer no solutions.

Below, I describe the sections of the dissertation in more detail.

Saturated Introduction

You are presently reading the saturated introduction.

Monounsaturated Introduction:

The monounsaturated introduction has two parts. It begins as a theoretical introduction to language in the context of concerns about the "computerization of society." It does this by teasing an influential report published in France (Nora and Minc's The Computerization of Society) in the late 1970s about its language— in particular the troubling status of the terms 'information' and 'communication.' The report was influential in France at a time when Minitel had started to appear, and is a reference point for a now more well known report by Jean François Lyotard. The point, therefore, of teasing the text, and more importantly, the introduction by Daniel Bell, is that it is an important foil for the concept of programmed langauge. Bell's introduction performs good little examples that serve to connect ordinary language and writing to software and to technical standards, without at any point recognizing the examples as such.

The second part tracks arguments by two theorists who should make my own arguments sound less outrageous. The well known report by Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition, is usually referenced as either a study of the "disappearance of Grand Narratives" or once again "the computerization of society" (which leans heavily on the above report for any actual computers). My focus, however, is on the report's programmatic statements about the need for a socio-political organization that is based on "legitimation by parology" with explicit reference to the function of "language games" as its basis. This, I insist, is a call for the abolition of intellectual property, and I hope to explain why, with reference to the dissertation, but without boring the reader to tears with details of Lyotard's argument. Opposite these themes, are those of Charles Sabel's work on what he calls "Learning by Monitoring" (on the new organizational structure of firms) and out of which he spins programmatic statements of reform that he refers to as "democratic experimentalism" and "directly-deliberative polyarchy". Sabel's proposals are by far the more detailed, and they amount to nothing short of a call for a new American government; sadly, these details find no home in this thesis. They are better saved for another project. What is more important to this thesis is that Sabel also insists on the importance of language to the new organizational forms that he identifies. Sabel's reference is pragmatism, especially those strands of pragmatism which he claims conceive of life and activity on the model of language (as a set of rules consistent enough to allow communication, but flexible enough to be modified in the face of ambiguity). Pragmatism, the history of the American regulatory state, and observations about "Learning by Monitoring" become important to this thesis as it nears its end, when I try to explain the reasons why Amicas is doing what it does now and here. My guide for this is Charles Sabel.

Polyunsaturated introduction

The thesis really begins in the polyunsaturated introduction— an ethnographic description of some corporations and hospitals developing information and communication technologies for healthcare. Polyunsaturated fats, I'm told, have on average more than one carbon-carbon double bond. Certainly strong bonds were formed with some in my field, but I prefer a more cis-literal meaning. Call them polyunsaturated facts— untheorized, unschematized, of diverse natures, liquid— an introduction to the nouns of my field, to the quotidian details and the unusual events, to the language of this there, and maybe to its boundaries (though I couldn't always find them). It begins there (your introduction does) because I want the reader to know where I was before the central Text of the dissertation was written. It is meant to program the reader with experiences that justify the see-sawings across the eclectic collection of disciplines, relevances, and arguments of the Text. They are essential facts, like essential fats, because a body can't manufacture them on its own, but needs to eat them. It is not, however, protein.

Such an ethnography is most recognizably a "Multi-locale" [Fischer90] or "Multi-sited"[Marcus94] ethnography. Having more than one site is a strategic research decision and in this case the very problem of locale recurses through this decision. There are several physical sites, most in the Boston area. Some are the various sites of the same company (Amicas, Inc.) some are the multiple clinics and hospitals of a single healthcare organization (Partners Healthcare System, including its two most well known hospitals— Massachusetts General and Brigham and Women's), some are the offices of individuals marginally connected to either of these places. In addition there are the connected hospitals and business outside of Boston and the sites of conferences and trade shows in Chicago and Atlanta (conferences representing a peculiar non-space of association by profession, less Atlanta or Chicago, thana "professional" home). Some sites are in foreign countries (Turkey, Greece, Saudi Arabia, Israel, India, Australia, Argentina, China), all of which sites yield their specificity "at a distance" via email, video conferencing and telephone conversations.

Something more than the difficult multiplicity of physical locations haunts this ethnography, however. Several "things" in my field are mysteriously unlocatable, or located no where in particular. Most importantly, the internet, but also, the economy, the market, the firm, the household, and culture. I defer answers until the Text, if only to attempt to give some sense of the confusion of being in the middle of these things— as an actor or as an observer. Several answers to this question of location, concerning principally the concept of scale (the intransitive verb, especially, as in "markets scale") will be given in the Text, Scale and Convention.

The bulk of this section will appear to be about a single company: Amicas Inc. It is. This is because I would like Amicas to stand in as a figure for the whole tangled array of people, things, places, and decisions that I was confronted with. Occasionally I will compare Amicas to The Partners Telemedicine Center at the Massachusetts General Hospital (part of Partners Healthcare System) which will often be Amicas' foil. Amicas concentrates questions concerning the location of the firm (including the hospital as firm, the firm as home, and the home as firm), the scale of the internet and the market, and the navigation of the myriad conventions of everyday life into a single figure. The folks who run this firm and write its software are at degree zero— if I take their words seriously, it is because I think they channel and process something much larger than themselves. I have found myself, at times, wanting to say something about the theoretical concepts of social theory, yet having no other word come to mind than Amicas. This does not mean they are exceptional, or alone— quite the contrary. Amicas may occupy a small market segment in a peculiar corner of the software industry with strange ties to a particular set of institutions, but this is incidental to the much larger set of concerns that occupy them: American start-up capitalism, entrepreneurialism, the internet economy (the "new" economy), the science and technology of digital imaging, economies of scale in software— including international business, the technical details of internet and healthcare standards, the relationship of academia to corporate America, fair allocation of access to medical technology, the source of value in software, the nature of property and its relationship to the contracts, licenses, and significantly for anthropology, to the gift. These are not concerns specific to Amicas, they are eminently 'academic' concerns. However, there is a related problem that studying a corporation makes explicit: the difference between understanding and doing. E.B. White's famous observation holds for corporations as well: "Analyzing humor is like dissecting a frog. Few people are interested and the frog dies of it." Solving problems, making things, creating value, effecting a change is the goal of corporate behavior. The 'profit motive' masks this expanded motivation as singular. This focus on doing, especially doing things with programmed language, is a concern for decision first and justification second [7].

Participating in such an environment therefore tends to look a little more like switching than fighting— especially from the perspective of an academic environment that seems to be focused either on willfully parochial enclosures of theory and research or disingenuous participation in an ever expanding economy of expertise [8]. However, at the point at which research encounters the experience of others, neither of these attitudes is acceptable as a strategy. On the one hand, the concept of "research" is overvalued in the corporate world, and the work produced in its name would never meet the standards of an academic conception of "research." On the other, academic research is to often confused by its desire to be objective, to maintain critical distance, and yet to still have an effect in the world. The spectrum of things that stretches from the "research" of Amicas to the "research" of economists or social scientists at a University is continuous, and I was just as often expected to contribute to one end, as I have been to the other. Critical distance, therefore, meets itself coming and going. The point is not that the point is not to interpret the world but to change it, but that the point is not to divide the world up into interpreting and changing, thinking and doing, saying and acting. I therefore offer Amicas as the figure for this challenge.

The scene setting of the Chapter A begins with Amicas and covers the details of the development of their technology at the Massachusetts General Hospital and its relationship to other technologies and other corporations involved in similar endeavors. It introduces some of the people with various degrees of detail. It ends with the movement of Amicas from MGH to Adrian Gropper's home. This movement is the reverse of most start-up companies, but as I explain, MGH was Amicas' garage, and Adrian's house (The World Wide Head Quarters) is the company's first sedimentation as a "real" company (as opposed to a "virtual" one).

Chapter B is a story, one I find particularly indicative. In Chapter C, I discover that one of the advantages of being involved on the ground floor of a start-up is closeness to the action. Many meetings that would be strictly inaccessible to anyone but the executives in any larger company, happened in public, because a virtual company has no boardroom. In this chapter I relate a particular meeting with some venture capital types as an example. This also leads to a meditation on the function of reputation, association, and networking and the slightly torturous story of my participation in this economy of reputation.

Sean Doyle is the person whose generosity made this study possible, and he is also the person whose creativity and intelligence make Amicas, the technology, possible. There are several stories and discussions with Sean in the thesis, but the most important, as in Chapter D, involve dinosaurs. Sean's eclecticism is energizing, and it served as a (re-)introduction to the functions of passion and humor in science and engineering.

Chapter E contains stories of the RSNA meeting in Chicago. Lurking as a foil to Amicas throughout the dissertation is another fieldsite that failed to yield anywhere as much energy, but perhaps as much experience: The Partners Telemedicine Center. This group is connected to Amicas technically, spatially, and in terms of personnel. In chapter F, I explain some of this history and how the configuration of the site as I found it came to be. Partners Telemedicine itself is detailed in Chapter G, including some of the most interesting stories I have from there. The Partners Telemedicine Center was in the unfortunate position of having little money for large ambitions, having poor management and high turnover of employees, and of being one of the few ships not lifted by the rising tide of the internet and the web. This section is anonymous for these reasons, and because it must serve as a foil here to what Amicas represents: the free-marketing of healthcare, and the replacement of the technical infrastructure of healthcare by the internet. It is not Partner's fault that these things happened, but in their status as victim of these changes, they occupy an important role, and it is worth telling the stories that occurred during this work.

Text: Scale and Convention

Each of the Chapters in this section has a short title and a Pooh-style subtitle of the major points of each chapter. They are reproduced here for clarity's sake.

In Brief: This Text introduces the primitives 'scale' and 'convention,' which circulate throughout the dissertation. There follows a literature review, an example, four chapters that attempt to present the details of standards, beginning from the fieldwork but extrapolating to standards in general, by virtue of an essential difference that is identified. There is an interlude before the narrative picks up again on one side of this essential difference— the internet and openness. Four chapters follow that narrate the wacky world of openness and its relation to scale and convention, via several prominent characters in the internet/free software/open world. There is then a second interlude before I pick up the question of value that I intend to answer by reference to Amicas and the business strategies and software design of Adrian Gropper and Sean Doyle. In order to set up this answer however, I attempt to fill in some of the historical, legal, and social theoretical details of the history of the American regulatory state and the American healthcare system and its infrastructure. This legal and medical history serves as an explanation of the political economy that explains why Amicas exists now, why it is engaged in a fragile attempt to create value in an unfamiliar way, and ultimately what this means for the organization of healthcare, the legal regime of property rights, and the configuration of international governance. The immodesty of these claims is tempered by the empirical research in healthcare, yet healthcare is not be treated as a peculiar institution here, rather, as one aspect of a market economy among others.

In Detail:

A. Introduction

Primitive operators 'scale' and 'convention' are introduced — Mice and Elephants compared in the context of scale, and related to discussions of the economy, the internet and Santa Fe — Scale becomes intransitive verb — Convention explained with respect to community, communication, empire, and telecommunications — the internet is identified as an Important Difference within convention — Convention and Scale form the beginning of a beautiful relationship — the location of the internet is sought, and not found — Various Philosophical Musings.

The Introduction uses an example from some "complexity" theorists of the Santa Fe Institute concerning the different sizes and metabolisms of animals to both explain the concept of scalability and to register its ubiquity as an analogy for internet startup firms. The concept of self-similar networks is often suggested as a model for the internet— in some cases is formalized as a mathematical problem— because it allows people to think about scale as an intransitive verb (e.g. "the internet server scales"— meaning it can handle a large number of transactions as simply as it handles one). The term convention is then introduced by reference first to scale (the present community vs. an international scientific community, for example), second with reference to communication and control, and its role in empire, and third as it relates to the convention (the technical standards developing processes) of the internet.

Scale and Convention have become the primitives of this dissertation because of the way that they change and challenge the notions of culture and locale, which might have been more familiar as anthropological notions. Scale is a better way of capturing what is usually attempted in the dual use of the terms 'local' and 'global' and any teratomas of that attempt, like "glocal." Convention, in my opinion, specifies what is important about how culture functions, and I try to justify this in various places in the dissertation. The emphasis on coordination is as important to social theory as it is to any theory of meaning, and 'culture' may suggest that, but only with great difficulty. I did not choose Scale and Convention initially to replace these terms, but upon reflection, realized that they might be usefully compared.

As a way of introducing the internet, I ask where it is. I ask this because I think that wherever it is, it is in the same place as the market (and sometimes 'the economy'), the public sphere and society. I do not intend to mystify the internet (and to this end I suggest some ways in which it has already been mystified by scholars— either as too material, or too metaphysical), but I do intend to suggest that it is not simply one technology (or place) among others.

B. Scholars wonder standards

In which a tangled bank of standards is discovered — their diversity is marveled at, then characterized by scholarship — a literature review is undertaken — an exemplary studier of standards is critiqued for whiggishness.

Chapter B is primarily a kind of literature review. I start from the assumption that conventions are everywhere ('standards' are the most familiar problems of technical coordination and production, and therefore to much of the literature in the history and social study of science and technology). Beginning with a philosophical distinction between nature and convention in Plato, I try to explain the basic structure of convention, its relationship to the decision, especially the decision to make something standard and to the subsequent use and legitimacy of that standard. Theodore Porter's work on mechanical objectivity assists me here in making these connections, as does Bruno Latour's focus on how something becomes accepted as scientific truth in Science in Action. I turn then to Ken Alder's work on standards for French artillery during the French revolution and find it extremely rigorous in all but one respect, his use of the term 'information technologies.' I object first because it obscures his argument that things and their representations were standardized at the same time (which would be a useful idea, if not so obscured), and second because I try to suggest that it is telecommunications itself which should be the model and sine qua non of an understanding of standards— not French guns, as he does— and that treating "information technologies" the way he does is anachronistic. I offer Friedrich Kittler as a counter-example that historicizes information technology too deeply, and find, ironically, that Kittler also refers us to a history of warfare as the essential ground of the competition of technical standards.

C. Exapple

A lowly apple is dissected for the purpose of explaining standardization's transformations in the 20th century — the imperative that drives these changes is sought, but not found.

Chapter C offers an example that tries to simultaneously bring together the problems of scale, convention and programmed language in a humble everyday apple and to suggest how standards might have evolved from the age of mass production (Alder's concern) to today. I pose the question of what it is that drives these transformations, and ask if one might be able to read them off something like an apple, or the Price Look Up sticker on the apple.

D. Economists ponder standards

Path dependency, increasing returns and network effects butt in — their sudden ubiquity in business is discussed — an example from the field is used to illustrate how 'standards' are now a common element in business strategy.

In chapter D, the literature review resumes, but with a difference. In the course of doing fieldwork and studying the internet economy, the terms path dependency, network effects, and increasing returns repeatedly appeared "in the field." The economic scholarship that concerns these words is a recent and fascinating set of theories (once again, partially derived from the Sante Fe Institute's focus on "complexity" theory) about the function of markets of goods that are constituted as networks that require compatibility of some kind (typewriters and typing teachers, computer software and computer hardware, videocassette formats— these are the conventional examples). These theories are little object lessons for actors in the internet economy, and it has become clear that technical standards, especially technical internet standards have become a strategic part of internet businesses. As an example, I offer a article written by Adrian Gropper that plainly emphasizes the importance of standards to hospitals considering buying a new PACS system. I explain how this story functions for him, how it circulates in the trade literature and that it relates to the Microsoft anti-trust suit as the government's first test of monopoly and anti-trust law on the internet.

E. Standard Differences

Scholarly literature is departed for an Example from ethnography — and Another from an email discussion on standards in which Religion and Heresy appear — some Very Important Distinctions are made — between freely available standards and not — between written standards and implementations — the concept "it works" is introduced and discussed.

Chapter E is an important chapter for understanding a crucial distinction between types of technical standards, especially with respect to the internet. I suggest that engineers and programmers from different traditions learn to relate to standards in different ways (in addition to simply learning different standards, given the enormous number of them). The first cut is to divide internet hackers from electrical and telecommunications engineers, which is simply a way of suggesting that the standards that govern the internet are only to be learned on the internet, while engineers trained or certified in a more traditional manner through classes and certification programs learn standards that way. The difference between these two forms of legitimacy is the difference between "it works" and legitimate authority in institutions of certification and teaching (the technical distinction is further explored in chapter G). I offer a particularly interesting email as an example of how this very discussion manifests itself on the internet, and how the contradictions and mysteries of the standards process are experienced. My 'evidence' for this distinction derives from my experience of it at Amicas and Partners Telemedicine (in the form of Sean as internet hacker and Tim O'Neil as electrical engineer). I offer some thoughts on the nature of the term "it works" and its difference from "it works well."

Further, two more important distinctions are made with respect to standards. 1) That between a freely available standard (which might or might not cost money) and an unavailable standard (such as a trade secret) and 2) that between a standard and an implementation of the standard. In the latter case, it is important to recognize that it is possible for an implementation of a technology (say, an application) to become a standard, and then be specified as such. This distinction is returned to in chapter H, with respect to the official bodies that set the standards. In this chapter, the examples of the Java and C programming languages, and compilers for those languages are offered as examples. These examples unravel themselves into a parallelogram of concerns that includes ownership, availability, workability, and national/international legitimacy.

F. Healthcare's Standards

A focus on healthcare — the knot of healthcare standards is partially unravelled — medical education standards and standards concerning specialties — the role of scientific authority in standards — scientific accounting — computers in medicine — clinical decision systems — technical standards and nomenclatures — the knot of healthcare standards is severed, leaving radiology standards — radiology workflow — diagnostic standards — DICOM takes up space — and time — informants are called upon to distinguish standards — Sean talks of DICOM and HTTP — Tim talks of IP and OSI — stupidity beckons.

Chapter F takes a sidestep into healthcare to explain the diversity of standards that exist in healthcare, in particular the chiasmic aspect of standards for "quality" and standards for technical or compatibility issues, which are constantly fading into each other. This fade-out can be seen in several examples from the history of healthcare, as well as the subsequent stories of them. I invoke the history of the standards for medical education and the Flexner report as an example of this double ideological and technical function of standards. I also look to the History of Medicine for further examples from the progressive era history of licensing, the college system, and the relationship between professional societies, hospitals and practitioners.

The growth of administration in this period (both in terms of organized corporate capitalism and the administrative growth in the government) affected healthcare in large and small ways. The examples of the adoption of Taylorism and scientific accounting are related to the infrastructure of healthcare, and to the growth of computerization and electronic medical records, all of which can be seen as imposing standards even as it uses them to ideologically legitimate specific kinds of change.

Clinical decision systems are also discussed before explaining the DICOM and radiology standards. The DICOM standard and its development is discussed briefly before returning to the explanations of Sean Doyle about the difference between DICOM and the protocols of the internet. His distinction is then opposed by the story of the engineer Tim O'Neil and his reasoning for the use of proprietary OSI-based networking in healthcare rather than the Internet Protocol (IP). Sean and Amicas are in the position of having to use both DICOM and the internet protocols, while Tim, whose work at the Telemedicine center also needed to be aware of DICOM but refused to use the internet protocols, because they sacrifice something "Quality of Service." Quality of Service concerns the integrity of data, and signals a concern for networks as "real-time" collaboration media rather than asynchronous collaboration media.

G. Stupid

An article from the field is used to explain some things — modernity and progress are related to standards for networks — differences between Other Networks and The Internet are stressed — questions are posed — a word becomes tiresome.

Chapter G returns to the distinction between the internet savvy people, and telecom/electrical engineers, this time in the context of an article given to me by Adrian Gropper that distinguishes between "stupid" and "intelligent" networks (the former is the internet, and no other, but the article typologizes).

In addition to clarifying the reasons why the internet is a different kind of network than all previous telecom networks, the article engages a discourse of modernity and progress that is peculiarly opposed to the kind of progress that the distinction it offers would imply. The concepts of abundant infrastructure, underspecification, and the particular importance of IP, the Internet Protocol, are all explained within this framework of progress and modernity. With tongue in cheek, stupidity is repeatedly called a desirable engineering value.

H. It works

The Internet Protocol is sought, and found! — detail about the distinction between paper standards and implementation standards is given — standards processes of ISO and ITU compared to those of ISOC — structure of ISOC and IETF explored — emergence of W3C wondered about — the politics of standards making is discussed and critiqued — TCP/IP is compared to OSI.

Chapter H accepts the challenge of stupidity offered by the previous chapter and asks, what, exactly it is that allows stupid networks to be stupid. The answer is found in IP, the Internet Protocol and this chapter endeavors to explain just how it works and for whom. I begin with a book by Schmidt and Werle that analyzes international telecommunications standardization in the 70's and 80's. Schmidt and Werle make sound analytic distinctions and give great detail about the two most important telecommunications standardization organizations: ISO, the International Organization for Standardization and ITU, the International Telecommunications Union. They discuss the organizational structure of ISO and ITU, both of which are firmly in support of a American and European consensus on trade liberalization and see standardization as a means to that end. The internet, however, they treat as just one network among others, and the Internet Society and its standards body, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) are called "parastandardization" bodies. This typology is appropriate to the period of research that the book covers, but clearly, since then, the internet has come to be something much more than just one network among others, and with it, its mode of standardization has become a well known style of standardization— at least for internet zealots. I try to give some detail about how this process works and relate that to the distinction that I identify in chapter E between "paper" standards and "implementation" standards, and in particular to the mechanism of political legitimacy implied by the IETF standards process and embodied in the phrase "rough consensus and running code," a synonymous sentiment to "it works." The chapter returns briefly to the question of the ISO-OSI standard raised in chapter F, and raises the question of the creeping power of the internet standards organizations and the people who participate in them. This power will be important for the concerns that follow in the next four chapters, about openness, and about the regulation of users on the internet by the internet.

I. Open Begin (various yarn)

A connecting interlude unravels — A section from Ellen Ullman's book Close to the Machine — a diversion on a piece by Robert Musil about doors and openness and design — an example of how programmed language has come to be expected, and how dissemination must be counter-programmed.

This interlude consists of three pieces that serve as a toggle between the five semi-expository chapters that precede it, and the four that follow, which focus in closely on the words and actions of certain personalities: Sean Doyle, Richard Stallman, Larry Lessig and Eric Raymond. First there is an excerpt from Ellen Ullman's novel/autobiography Close to the Machine, which tells a brief parable of "it works." Ullman's book is an indispensible reference to the emotional life of software, to the lyrical expression of work, and to some gritty details of life in Silicon Valley.

In the second piece, I reflect on Robert Musil's short piece "Doors and Portals" for what it reveals about the relationship between two things: openness and design. Most of the four chapters that follow, deal with the vicissitudes of the term "open" but never with the kind of clarity that Musil's piece offers for the door. The door represents the boundary between public and private for Musil— a boundary he says is no longer operative. The variety of uses of the terms open and closed could all have been condensed into this figure of the door (e.g. Max Weber on open and closed societies, Karl Popper's Open Society, Elias Cannetti's open and closed crowds, Alexandre Koyre's closed worlds and open universes, the list goes on and on). More importantly than simply being a figure for open and closed, however, the door figures design as essential to the distinction. In the same way that Walter Benjamin's Passagenwerk steals through the streets of Paris connecting personalities and architectural phenomena into a meditation on the progress of history, Musil's piece imagines the space between inside and outside that the door had once so clearly ordered and controlled as a hole "still left open to the carpenter." I insert it here, because the following chapters make liberal reference to concepts and uses of openness that I try to critique or object to, and ultimately, to explain.

The third piece is an example of programmed language, and a peculiar one at that. It is an excerpt from an SEC filing for an Internet startup company's IPO, available on the SEC's Edgar service. It is something J.L. Austin would be thrilled by, I imagine. It attempts not so much "to do things with words," as to warn people that words don't always do things, and thereby to do something: reduce liability. The particular words it worries over— anticipatory, promissorial words— are precisely those words that signal an irreducible openness that can only be incompletely captured, by other words, or by risk profiles.

J. Source and Passion

Open source appears suddenly, frightens some — opensource.org and the Free Software Foundation are distinguished — Sean's words noted as the experience of one 'hacker' — hacker authenticity considered — the relentless myth of scientific method is identified and dismissed as ideology — Sean's experience a counter-proposal to the scientific method myth — the excitement of learning and sharing identified as An Important Thing — Heidegger referenced.

This chapter introduces the organizations opensource.org and the Free Software Foundation, via some discussions with one of my informants, Sean Doyle. I have tried to explore how Sean's experience of the internet, software design, science, and academia fits uneasily with the common narratives and marketing proposals that surround the "open source revolution." This is difficult to do without obscuring the fact that Sean is very excited by the prospects of using "open source" as a business model and has in fact benefitted from something on the internet that, while it may not be just the way "open source" people say it is, is still substantially different from other versions of research and science that happen "off the internet". The details of this difference concern the separation by academic discipline, by place (Sean worked at the Federal Reserve Board, a place rarely identified as a hotbed of hacker wackiness), and by platform (machine or operating system).

Opensource stories inevitably begin with some version of a myth of the "scientific method" either to explain what are seen as similar principles, or to justify the movement by reference to the ideological power of science. I suggest that the power of the scientific method as a myth obscures the very real connection that the internet has had over its 30 years to the institutions of science, and to try to explain, via the example of Sean, how such a connection can yield an experience of science as a valuable exercise in sharing knowledge and collaborating in an ad hoc manner— not exactly a vocation rooted in ascesis. The "communities" that form are fragile, formed only to solve a given problem, and once the problem is solved, abandoned for new problems. This mode of research is significantly different from what I try briefly to relate to Heidegger's understanding of science and research as "putting in reserve." Though the chapter would need to be significantly expanded in order to explore whether this difference is ontic or ontological (to use his terms), I prefer to stick with Sean, for now, as both explanans and explanandum.

K. Geek Programs Law

Opensource.org and The Free Software Foundation further distinguished — opensource.org attacks FSF — Richard Stallman explained — FSF's veritable political actions in licensing is contrasted with Stallman's incessant talk of freedom — FSF critiqued — the distinction between the technical and the nontechnical is identified as A Major Problem --FSF attacked by opensource.org, again — opensource.org is called disingenuous by the author.

In chapter K, I begin with the reasons why an "open source" model of software development are appealing to Sean and to Amicas. They include real and calculated concerns about Microsoft products, and about the political implications of Microsoft's strategies. The difference between opensource as a better software design tool, and open source as "free software"— a political stance— is the difference between a deliberately political economy, and just an economy. I begin the exploration of this difference with Richard Stallman and the Free Software Foundation, often identified as the origin of all subsequent free software and open source initiatives. Stallman's storied life in hackerdom experiences, crucially, the break up of the MIT AI lab community and the "commercialization" of software. Since that time, Stallman has been a very vocal proponent of "free software". His political speeches and manifestos detail his positions and harp on the importance of "values" (such as freedom) that he insists, in good classical liberal form, must be discussed and circulated lest they be forgotten. However, in contrast to this political speech is the political action of the FSF's General Public License, which manipulates copyright and contract law to guarantee that the software it licenses will never be owned by anyone (by effectively nullifying copyright law with contract law). This maneuver, I suggest, is akin to programming the legal system like a giant computer, to do something very clever, it is a Hack.

The chapter then proceeds to a discussion of some of Stallman's writings with this fact in mind. Stallman's justifications of when something should be copyrighted and when it shouldn't depend on an arbitrary distinction between the technical and the non-technical that is unsupportable in any absolute sense, but only decidable in each specific instance. The distinction technical/non-technical then becomes the hinge on which property swings, and it swings towards contract, and away from copyright.

The differentiation of opensource.org from FSF, and the bitter denunciations by the former of the latter are part of what will be called later a "corporate reconstruction of capitalism" in which opensource.org participates with the fanaticism of converts. Opensource.org has successfully shifted the discussion away from "freedom" and politics, to that of business models and marketing, but this is ideological packaging for the weakening of vigilance over the attention to licences that the FSF performed. In particular opensource.org abandons a vigilance over the structure of licences and the terms of contract in favor of an even weaker version of IP law, namely trademark law. This weakening leads the direction of a strengthened commercial contract law, compounded with the protection of intellectual property law that could be used to elaborately control software. This maneuver, by opensource.org, is therefore a disingenuous disavowal of politics that hides a strengthening of both property and contract rights of software corporations.

L. Lawyer worries nature

Law is consulted on the subject of convention — Larry Lessig takes the case — Lessig's work critiqued — some ideology surrounding the regulability of the internet is denounced — 'Nature' identified as culprit — Lessig replaces nature with code — values are sought, but not found — the first person plural becomes very annoying — an aporia of value is stumbled on — the forgotten role of government is remembered — "We are the World" — the values of the internet are identified by Lessig and proposed as a new constitution — efficiency is decried as an inadequate value.

Chapter L is an investigation of Lawrence Lessig's work on and participation in this field of internet law and politics. He is consulted as a lawyer not for an explanation of what is going on, but as an example of how one lawyer has come to participate in it. Lessig's writings offer a partially convincing explanation of how "regulation" works (in the expanded sense of "rules that govern behavior"), especially, how the code of the internet regulates users. The discussions tend to be more rhetorically edgy than classically argumentative, but nonetheless manage to stumble onto the very problem of the source of values in regulation that I identify with Jacques Derrida's essay "Force of Law", that is to say, the regulating/regulated aporia of value. This discovery is significant because it raises the question of the first person plural explicitly. Lessig constantly returns to a "we" who don't want "our" government messing with things. Yet this "we" on the internet is no longer the "we" of America, and Lessig realizes this. The problem Lessig raises is therefore a problem of international, not national governance.

This discovery, significant in itself, is complicated by the fact that Lessig uses the open source movement as a figure for a revolution in "openess" that he represents as a political platform for the recovery of values and the potential regulation of the internet. This puts the reader at the mercy of a language that is hype, marketing, and political speech at the same time. Lessig identifies what he says are the "values" of openness in cyberspace— he calls them "open forking" and "universal standing" but misses the fact that it is openness itself here, not these values, that legitimates the openness of the internet. One thing Lessig does not miss, however, is that opensource.org doesn't care about these values, but rather, about the fact that open source software is more stable, robust, and efficient than commercial software; and Lessig knows this is not a sufficient value for a democratic revolution.

M. Anthropologist seeks navel

Eric Raymond, libertarian anthropologist assessed — Stallman attacked, again — Raymond's various writings discussed and critiqued — several crucial insights about property and legitimacy in open source gleaned — the gift appears, and is examined for its contents — reputation identified as the source of value — questions remain.

Chapter M returns to the ostensible, disavowing organizer of opensource.org, Eric Raymond. Raymond is a peculiar figure, no one's hero, but everyone's leader. He has played a remarkable part in bringing the model of open source software development to the attention of business and the media. His attacks on the FSF and his disingenuousness about his own political role are features of this chapter, which is highly critical of Raymond's words. At the same time, however, Raymond figures himself as an anthropologist, and in the course of his "fieldwork" has unearthed several fragments of the "culture" of hackers, that are worth pondering. Two of Raymond's articles are discussed then, the most famous being "The Cathedral and the Bazaar" which elaborates on the mechanisms of an open source software development model. For anyone unfamiliar with "open source," this is considered essential reading. The other is an article entitled "Homesteading the Noosphere," which attempts to formalize some observations that Raymond makes about property customs in cyberspace and the function of a "gift culture" among software designers. To this last point I am unable to resist responding, and rather than savaging Raymond's misunderstanding of the gift, I try a counter-example: Sean Doyle's occasional musings and comments on "giving back."

The chapter ends by focusing on Raymond's assertions that the economy of open source occurs by reference to a structure of reputations that provide real and symbolic value to participants.

N.Open End (a ligature)

A second connecting interlude flexes — Ellen Ullman cynicises — some arguments are recapitulated — the reader is warned of the author's attitudes — Amicas is reintroduced — Amicas's values posed as question — culture avoided in favor of story.

This interlude binds the middle four sections to the last three by returning from the land of openness to the specific example of Amicas and the histories of property, the regulatory state, and the healthcare infrastructure. The piece by Ullman marks the interlude in the same way as the previous one, but this time pointing forward to the relationship between revolutionary rhetoric, hype in the software industry, and the regrets of an erstwhile socialist software engineer.

Explaining the political economic conditions of possibility of Amicas, or any other internet company, and the people involved, is a difficult endeavor. To do so with the tools of anthropology and science studies, perhaps impossible. At bottom, I think there is a simple question of explaining what is going on, and how people are doing it, before any possibility of critique. In the case of Amicas, I learned enough about a particular aspect of healthcare (radiology imaging and healthcare information technologies) that I could put myself in Amicas' position and experience their activities as the solution to a difficult problem coupled with a desire to create value (which does not always mean 'make money'). This fact, I think is what demands critique, and this interlude introduces the chapters that open up the route to that critique. Furthermore, it is no longer meaningful to me to call such critique "cultural," and I try to explain why here, and what America means to Amicas and the internet, if it isn't "culture."

O. Properties of Americans

James Livingston and Martin Sklar join the author in a round of history — basic details of late nineteenth century corporate capitalism related — the legal status of property as rights and the creation of a regulatory state are identified as Important Related Subjects — Morton Horwitz joins the party — Significant Articles in the history of property law cited — institutional economics tapped — Charles Sabel joins the party and Stays Late.

In chapter O, I return to Amicas, to explain at least partially, in a larger political economic sense, why they can exist now, and what historical events are essential to this possibility. In order to do this, I rely on two historians, Martin Sklar and James Livingston, to tell the history of a late nineteenth century change in American corporate capitalism (with occasional reference to alternative stories by Karl Polanyi and stories derived from Marx). The changes that they identify are legal and regulatory changes, and a crisis of consumption that led to a changed notion of value, shifting property rights in the direction of intangibility. I also rely on Morton Horwitz's histories of the transformation of law to add detail to this story. I retell in particular the narrative of the transformation of the concept of property in the nineteenth and twentieth century from a question of "customary value" to a bundle of rights in a thing, tangible or intangible. This transformation in property rights allowed what Sklar calls "a corporate reconstruction of American capitalism," and what Livingston identifies as a "cultural revolution" in the subjectivities of people confronting a changed capitalism.

In addition, the change in legal conceptions of property was concomitant with the rise of the administrative and regulatory regime of the American government. The creation of these regulatory agencies were much promoted and discussed during the progressive era by reformers, economists and the American Legal Realist school of Law. The delegation of power from public government to private citizens is identified here as the crucial change in governmental structure, one that has become painfully obvious since the seventies, as regulatory agencies and administrative bureaucracy have grown to positively unwieldy sizes while simultaneously being criticized relentlessly for their meddlesome inefficiency and interest group politicking.

Enter Charles Sabel and "Learning by Monitoring." Sabel's solutions to these problems reach beyond the bounds of this admittedly expansive dissertation, and should make the claims made here look modest. His studies of automotive firms and the disciplines of "simultaneous engineering" and "learning by monitoring" are identified here in their similarity to what Amicas does. In particular, though Sabel does not emphasize it, there is a relation to the standards for both healthcare and the internet. Sabel refers to a "single language of practical reason" (by reference to the Pragmatists Dewey, Mead, and Peirce) that allows people in "disciplines with similar syntax" to conduct meaningful explorations of possibility (economic and design possibilities in the case of firms). I suggest that this syntax is standards, in particular standards for the internet (or standards for networks and software more generally). Sabel's claims are not restricted to economic organization, however, but are suggested as a manner of reforming the American regulatory state, and in it's strongest form the constitutional government itself ("A constitution of democratic experimentalism" with Michael Dorf).

P.Infrastructure

Rosemary Stevens joins the author in a last round of history — social insurance and the Blues are sung — Medicare, utilization review and DRG's identified as Important Changes — investor-owned hospitals and HMO's tapped — Charles Sabel returns to discuss guiding rules, tacit norms and fixed costs — Adrian Gropper enters — Adrian's notion of infrastructure dissected.

In Chapter P, I return to history again, this time to specify the history of the American healthcare industry. Rosemary Stevens is the best guide here, and one of the only ones whose work extends close enough to the present to capture the important recent changes. It supplements a larger history of healthcare focuses on the Hospital and it makes a strong case for something I think is crucial to the contemporary attitudes of healthcare internet start-ups: that the technological infrastructure of the hospital is its product. To this end I trace some of the important infrastructural changes in the political economy of American healthcare in the twentieth century. These include the Hill-Burton acts, Medicare, investor-owned hospitals, utilization review and DRGs (Disease Related Groups). If, as Stevens suggests, infrastructure is the product of American healthcare, and as Sabel suggests, new forms of economic organization focus on reducing fixed costs, then there is a potential breach here that I suggest Amicas fills, as a representative of internet healthcare.

After this specification of the existing infrastructural configuration of healthcare, I reintroduce Adrian Gropper, via a set of interviews in which he tries to explain his strategy and the status of the healthcare information systems industry and in particular the radiological information systems and PACS industry. Adrian distinguishes this field into three players that become essential to his understanding of how the internet can come to replace the infrastructure of the healthcare industry. It is from the perspective of the internet as a non-industry-specific solution to all problems of information communication that Adrian positions Amicas as a solution to the workflow problem in radiology, and in the hospital at large.

Q. Integrated

The author's other life is revealed — consensus on "integration" explained and critiqued — the irony of this consensus is noted — Adrian explains The Big Picture — systems integration is taken to task by Adrian — consulting is probed and prodded — consulting considered as an Important Substance in fluid programmable capitalism — the internet is posed as a solution — — the healthcare crisis is solved by Adrian and the author.

Chapter Q focuses almost entirely on Adrian's strategies and explanations. I raise the question of whether this is a representative view by reference to my own participation in the promulgation of it as an occasional contributor to a major research publication. I identify a kind of consensus— a sort of convention— that is widespread enough that I could channel it into several articles without any real understanding of what it referred to or where it came from (of course, this suggests that I do now, which is only partially true). This consensus concerns the story of the "integration" of healthcare and the irony of this honest desire (this consensus is not unrelated to that identified by Bonnie Kaplan in the concern over "lag" in medical computing).

I allow Adrian to set up "the big picture" in healthcare according to his tripartite distinction from chapter P. Adrian explains why certain models of "service" are broken, or reduce to consulting, and why Amicas is both a product and a service, but neither broken, or simply consulting. Consulting firms are then considered as a crucial component in the current "Learning by Monitoring" economy as a kind of caulk that solves just enough of a problem to prevent leakage.

As a tantalizing final section to the dissertation, Adrian suggests how he thinks the healthcare crisis (i.e. it's disorganization with respect to information, cost and fair access) should be solved.

R. Conclusion

Chapter R is a conclusion, an unusual device found rarely these days that attempts to "tie it all together." This one doesn't yet exist.

Last Modified 11-Sep-99 9:27 PM ckelty@mit.edu

Go Back to the Start